No Child Left Behind turned 20 this year

The policy has been replaced by ESSA, but it's disastrous legacy lives on

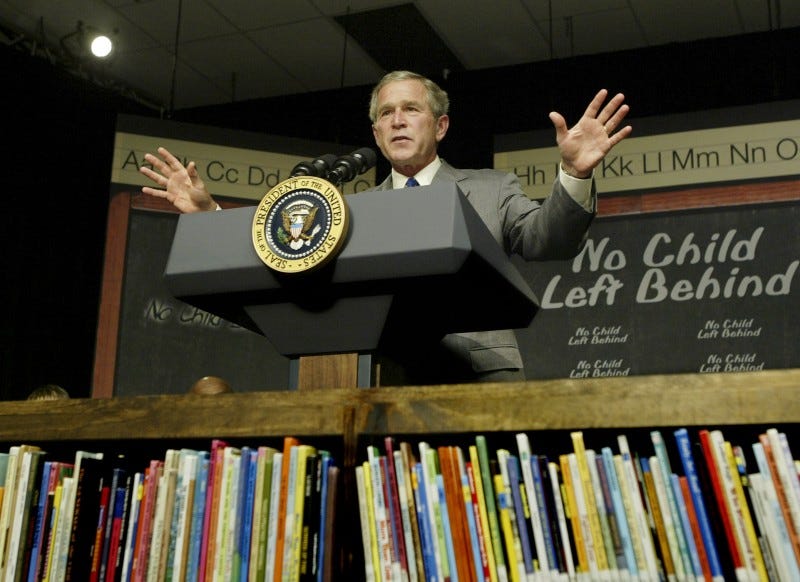

“I've come to herald the success of a good piece of legislation. I have come to talk to our citizens about the results that this reform has yielded. And I call upon those who can determine the fate of No Child Left Behind in the future to stay strong in the face of criticism, to not weaken the law—because in weakening the law, you weaken the chance for a child to succeed in America—but to strengthen the law for the sake of every child.” - George W. Bush, January 8, 2009

This holiday season, give the gift of EduThirdSpace. If you routinely learn something new from this newsletter and think a colleague, family member, or friend would also value the content, spread the love by gifting a subscription.

No Child Left Behind, one of the most influential education policies in U.S. history, was passed 20 years ago. The Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) replaced NCLB in 2015, but the legacy of the legislation lives on. To celebrate the landmark policy, I present my criticisms. Again.

The No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB) was passed with bipartisan support and signed into law in 2002, during my freshman year of college. At that time, I was in the process of switching my major from psychology to elementary education. I knew little about the implications of the legislation because I had completed my K-12 schooling without it. Within the school of education I attended, the policy was constantly scrutinized, and upon graduation and securing a teaching position with Chicago Public Schools, I began to find that many of the complaints were warranted.

The overarching goal of NCLB was to have all public school students across the U.S. achieve proficiency in reading and math by the 2013-2014 school year. Proficiency was measured by a standardized test chosen, with federal government approval, and administered by each state in grades three through eight and once in high school. If a school did not meet the benchmarks set forth, they were at risk of losing funding, losing staff, or school closure—in other words, the stakes were high. Another key component of the legislation was the evaluation of teachers. To varying degrees, depending on the state and school district, teacher evaluations were tied to student performance on the yearly standardized test. By the time the ESSA was enacted in 2015, no state had achieved the proficiency standard.

I taught in the early years of the legislation, and they were stifling. I worked in high crime, high poverty neighborhoods where low academic achievement was a persistent problem. As such, both schools I worked at placed a heavy focus on ensuring students performed well on the tests to the point where teaching to the test and test prep in the form of completing worksheets was the norm. All of the creative juices I harnessed during my college elementary education program were for naught.

I don't have a problem with standardized assessments per se. I have no issue with high school graduation exams, the ACT, SAT, assessments to enter graduate school, or even the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP; the nation's report card). They all tell us something useful about student ability and student preparedness for subsequent endeavors. And I understand why we don't want to wait until high school to learn that students lack crucial skills.

My gripe is with yearly high stakes standardized tests that are more often used to measure teacher performance than as diagnostic tools to improve student learning, which is what became of yearly testing after NCLB was enacted. I also take issue with the high stakes nature of the tests because, as I have written about elsewhere (see here, here, and here), as have others, achieving equality of outcomes is not possible given that student ability varies, thus the legislation set teachers and schools on a road toward failure from the get-go. For example, the school where I taught 5th grade split students by ability level, and I was assigned to teach the lower achieving class. Sadly, they were never going to match the test scores of the neighboring, higher achieving 5th grade class, and the students in my class knew it. This was demoralizing for them as students, and humans, and for me as the teacher whose evaluation, in part, relied on them successfully passing the test.

The tests are also demoralizing because they conflate in the minds of children high scores and individual worth.

Teachers of tested grades (3rd - 8th) rotate classrooms to proctor the test (teachers are not allowed to monitor their own class during testing). One year, I ended up in a 4th-grade class, where I had to console a hysterical student who was worried she was going to fail the test. This 10-year-old took her performance on this one test to be some sort of indictment of her character—who she was as a student, and a person.

The climate that surrounds testing season gets so tense that teachers read books to soothe students’ anxiety, and their own. Testing Miss Malarkey is a popular choice:

"The new school year brings standardized testing to every school and Miss Malarkey's is no exception. Teachers, students, and even parents are preparing for THE TEST-The Instructional Performance Through Understanding (IPTU) test-and the school is in an uproar. Even though the grown-ups tell the children not to worry, they're acting kind of strange. The gym teacher is teaching stress-reducing yoga instead of sports in gym class. Parents are giving pop quizzes on bedtime stories at night. The cafeteria is serving "brain food" for lunch. The kids are beginning to think that maybe the test is more important than they're being led to believe. Kids and adults alike will laugh aloud as Finchler and O'Malley poke fun at the commotion surrounding standardized testing, a staple of every school's year."

Everyone in the school knows the stakes are high, and great relief spreads throughout the school when testing season is over. The relief is a sign that everything done that school year was in the service of the test—all the books read, math problems solved, and essays written. The message is clear: learning is for the sake of the test, not for the sake of itself.

Much of the recent rhetoric around getting rid of NCLB-era standardized tests has been placed under the banner of anti-racism, when in reality many have long-pointed out the issues these tests have created. Famously, Diane Ravitch, an architect of the policy, is one such critic. Now, whenever there are legitimate complaints about the policy and how to shift in a different, more productive direction, such as by instituting a competency-based learning model, accusations that critics just want to lower standards start mounting. To be sure, the anti-racism policy proposals surrounding schools certainly sound like calls to lower standards, and probably are in some cases, but not all critics of high-stakes standardized assessments want the end result to be lower standards. I want quite the opposite. I want the bar to be high, but set using models that encourage students to acquire a wide breadth of knowledge and skills, not by teaching to tests that measure how one student or group of students compare to another.

I worked in schools that year after year straddled the pass/fail line, but the problems that stem from NCLB are not exclusive to persistently low performing schools. A friend of mine (who I'll call Jane) has daughters in one of the top performing districts in her state. The pressure is there as well, just in a different form. Under the mandate to consistently improve performance from one school year to the next, high performing districts can't just sit back and relax knowing their schools are no where near failing, they have to push them to achieve higher marks than the previous year. One of Jane's daughters couldn't stomach getting anything below an A; when the bar got higher, so did her stress level. Jane's other daughter was consistently a C student no matter how hard she tried, thus she often came home feeling like a failure. Another friend with a daughter in an affluent, high-performing district has told me stories of the façade of the district’s high performance. Her daughter and her classmates are given multiple opportunities to redo assignments and course exams to boost their grades and better prepare for standardized assessments. The critics of anti-racist school policies bemoan these sorts efforts to lower the bar for non-white students in low performing schools, but they are happening everywhere.

The incentive structure is perverse. If the future of a school or teacher hangs in the balance, of course the administrators and teachers are going to utilize whatever tools are at their disposal to ensure students do well on these tests. And doing well often doesn't equate to a high-quality education. Classical education, for example, is making a comeback as a means to provide students with a more well-rounded education that emphasizes knowledge acquisition, but if such an education is offered in a charter school, it is susceptible to the same problems. Charter schools trade greater accountability for more autonomy in governance, thus the pressure is even higher for their students to perform well on standardized tests. As a result, what one thinks of as a classical education—seminars run using the Socratic method—is rare in such schools because that sort of teaching method does not line up with the expectations of the test.

From the outside, complaints about NCLB and the resulting testing regime may seem like whinny teachers who don't want to be subjected to evaluations. And in some cases they are probably correct. The upside of NCLB is that it did illuminate the poor teachers who needed to leave the classroom for the sake of the students. And there are exceptional teachers who deliver content in ways that don't strictly center everything around the test. But the measure of all learning and success in a school cannot be told by a standardized yearly exam. NCLB perverted teaching and learning. That is its greatest accomplishment.