What killed Socrates?

His unending pursuit of the truth

Socrates was sentenced to death because he saw the light and dared to reenter the cave.

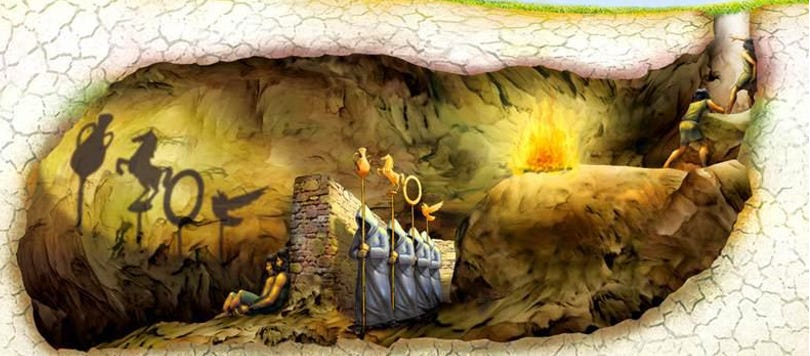

In Plato's Republic, Socrates asks his interlocutors to imagine that a lack of education is analogous to living in a cave, where prisoners must keep their heads motionless throughout life. They can't look around, they don't ask questions, they can't even look at themselves or their neighbors. They only see and know what is projected in front of them. That is their truth, the shadows of the artifacts shown before them.

"Imagine human beings living in an underground, cavelike dwelling, with an entrance a long way up, which is both open to the light and as wide as the cave itself. They've been there since childhood, fixed in the same place, with their necks and legs fettered, able to see only in front of them, because their bonds prevent them from turning their heads around. Light is provided by a fire burning far above and behind them. Also behind them, but on higher ground, there is a path stretching between them and the fire. Imagine that along this path a low wall has been built, like the screen in front of puppeteers above which they show their puppets. [...] Then also imagine that there are people along the wall, carrying all kinds of artifacts that project above it--statues of people and other animals, made out of stone, wood, and every material. And, as you'd expect, some of the carriers are talking, and some are silent."

Socrates then asks his interlocutors to imagine that one of the prisoners was freed and brought out of the cave, into the light, and cured of his ignorance. The light represents the truth, while the darkness is their ignorance. Socrates asks, when the prisoner first sees the light, "wouldn't his eyes hurt, and wouldn't he turn around and flee towards the things he's able to see, believing that they're really clearer than the ones he's being shown?"

Wouldn't he default to what he had been shown and thought to be true all of his life?

On the other hand, what if he accepted the light to be the path to truth, and perhaps discovered the truth, then returned to the cave to tell the other prisoners? "Wouldn't it be said of him that he'd returned from his upward journey with his eyesight ruined and that it isn't worthwhile even to try to travel upward?" And wouldn't he be ridiculed and punished for going against what he had learned in the cave? To avoid such punishment and ruin, such destruction of their ignorance, their version of the truth, wouldn't they resist being removed from the comfort of the cave? And, Socrates asks, wouldn’t anyone who tried to free the remaining slaves and lead them upward toward the light be killed?

Socrates was a lover of wisdom, a philosopher, and thought that everyone should take the upward journey toward the light, despite any negative consequences. He went seeking out anyone, citizen or stranger, whom he thought wise, especially those who were public figures and proclaimed to be wise. He met his fateful death because, in this pursuit, if it turned out that the person was not wise, he returned to the cave—in other words, he showed him that he was not wise through questioning and pointing out illogical arguments.

In Plato's Apology, Socrates, on trial, says he would do it all over again if given the chance. He would continue to ask questions and seek the truth because "the unexamined life is not worth living for man." He submits that it's likely that neither he nor those who claim to be wise know anything worthwhile. The difference between himself and the supposed wise, Socrates points out, is they think they know something when they do not. Socrates, on the other hand, does not think he knows what he does not know.

Socrates' sentence of death by the state for, ultimately, questioning then exposing those who claim to be wise but are not mirrors modern attempts to censure. Those who walk out of the cave, toward the light—who seek to understand multiple perspectives on an issue and question truth claims doled out by those in positions of authority—then return to the cave to educate the masses are punished. They are publicly shamed, have their livelihoods taken away, and lose their jobs. They are called conspiracy theorists.

Claims of certainty are driving their censors. When in reality, there's often not enough information to make proper judgment.

The dialectic exemplified by Socrates, often referred to as the Socratic method, acknowledges and leans into uncertainty. The capital-T Truth is not something that any one person has, and the Socratic method allows those who believe the Truth exists to pursue it in concert with others. The pursuit is ongoing and may never be achieved. It requires the embrace of uncertainty and the willingness to acknowledge that you might be wrong. Current discourse is severely lacking in this regard; one cannot even ask questions.

There is no education if we are banished to the cave.