A "Children's House"

From "Dr. Montessori's Own Handbook," by Maria Montessori

Maria Montessori’s method for education is nearly ubiquitous in early childhood education. School’s have formed in her name or claim to follow her method and toys have been created using her ideas. I wrote about Montessori’s views on education in a subscriber-only post. This post is the first of 10 in the “Education, Serialized” series sharing Montessori’s book, Dr. Montessori’s Own Handbook, first published in 1914.

The “Children’s House” is the environment which is offered to the child that he may be given the opportunity of developing his activities. This kind of school is not of a fixed type, but may vary according to the financial resources at disposal and to the opportunities afforded by the environment. It ought to be a real house; that is to say, a set of rooms with a garden of which the children are the masters. A garden which contains shelters is ideal, because the children can play or sleep under them, and can also bring their tables out to work or dine. In this way they may live almost entirely in the open air, and are protected at the same time from rain and sun.

The central and principal room of the building, often also the only room at the disposal of the children, is the room for “intellectual work.” To this central room can be added other smaller rooms according to the means and opportunities of the place: for example, a bathroom, a dining-room, a little parlor or common-room, a room for manual work, a gymnasium and restroom.

The special characteristic of the equipment of these houses is that it is adapted for children and not adults. They contain not only didactic material specially fitted for the intellectual development of the child, but also a complete equipment for the management of the miniature family. The furniture is light so that the children can move it about, and it is painted in some light color so that the children can wash it with soap and water. There are low tables of various sizes and shapes—square, rectangular and round, large and small. The rectangular shape is the most common as two or more children can work at it together. The seats are small wooden chairs, but there are also small wicker armchairs and sofas.

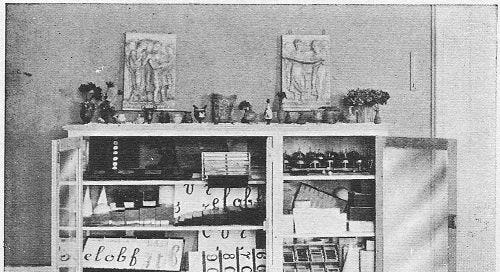

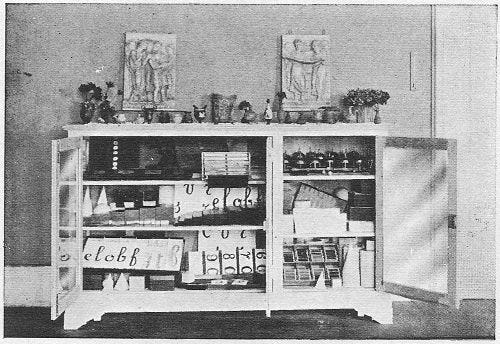

In the working-room there are two indispensable pieces of furniture. One of these is a very long cupboard with large doors (see image above). It is very low so that a small child can set on the top of it small objects such as mats, flowers, etc. Inside this cupboard is kept the didactic material which is the common property of all the children.

The other is a chest of drawers containing two or three columns of little drawers, each of which has a bright handle (or a handle of some color to contrast with the background), and a small card with a name upon it. Every child has his own drawer, in which to put things belonging to him.

Round the walls of the room are fixed blackboards at a low level, so that the children can write or draw on them, and pleasing, artistic pictures, which are changed from time to time as circumstances direct. The pictures represent children, families, landscapes, flowers and fruit, and more often Biblical and historical incidents. Ornamental plants and flowering plants ought always to be placed in the room where the children are at work.

Another part of the working-room’s equipment is seen in the pieces of carpet of various colors—red, blue, pink, green and brown. The children spread these rugs upon the floor, sit upon them and work there with the didactic material. A room of this kind is larger than the customary class-rooms, not only because the little tables and separate chairs take up more space, but also because a large part of the floor must be free for the children to spread their rugs and work upon them.

In the sitting-room, or “club-room,” a kind of parlor in which the children amuse themselves by conversation, games, or music, etc., the furnishings should be especially tasteful. Little tables of different sizes, little armchairs and sofas should be placed here and there. Many brackets of all kinds and sizes, upon which may be put statuettes, artistic vases or framed photographs, should adorn the walls; and, above all, each child should have a little flower pot, in which he may sow the seed of some indoor plant, to tend and cultivate it as it grows. On the tables of this sitting room should be placed large albums of colored pictures, and also games of patience, or various geometric solids, with which the children can play at pleasure, constructing figures, etc. A piano, or, better, other musical instruments, possibly harps of small dimensions, made especially for children, completes the equipment. In this “club-room” the teacher may sometimes entertain the children with stories, which will attract a circle of interested listeners.

The furniture of the dining room consists, in addition to the tables, of low cupboards accessible to all the children, who can themselves put in their place and take away the crockery, spoons, knives and forks, tablecloth and napkins. The plates are always of china, and the tumblers and water-bottles of glass. Knives are always included in the table equipment.

The Dressing-room. Here each child has his own little cupboard or shelf. In the middle of the room there are very simple washstands, consisting of tables, on each of which stand a small basin, soap and nail-brush. Against the wall stand little sinks with water-taps. Here the children may draw and pour away their water. There is no limit to the equipment of the “Children’s Houses” because the children themselves do everything. They sweep the rooms, dust and wash the furniture, polish the brasses, lay and clear away the table, wash up, sweep and roll up the rugs, wash a few little clothes, and cook eggs. As regards their personal toilet, the children know how to dress and undress themselves. They hang their clothes on little hooks, placed very low so as to be within reach of a little child, or else they fold up such articles of clothing, as their little serving aprons, of which they take great care, and lay them inside a cupboard kept for the household linen.

In short, where the manufacture of toys has been brought to such a point of complication and perfection that children have at their disposal entire dolls’ houses, complete wardrobes for the dressing and undressing of dolls, kitchens where they can pretend to cook, toy animals as nearly life-like as possible, this method seeks to give all this to the child in reality—making him an actor in a living scene.

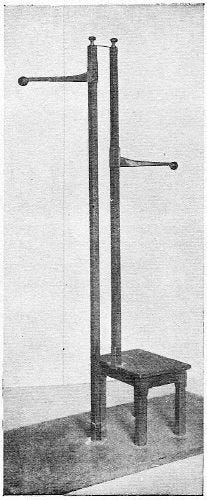

My pedometer forms part of the equipment of a “Children’s House.” After various modifications I have now reduced this instrument to a very practical form (see image above).

The purpose of the pedometer, as its name shows, is to measure the children. It consists of a wide rectangular board, forming the base, from the center of which rise two wooden posts held together at the top by a narrow flat piece of metal. To each post is connected a horizontal metal rod—the indicator—which runs up and down by means of a casing, also of metal. This metal casing is made in one piece with the indicator, to the end of which is fixed an india-rubber ball. On one side, that is to say, behind one of the two tall vertical wooden posts, there is a small seat, also of wood. The two tall wooden posts are graduated. The post to which the seat is fixed is graduated from the surface of the seat to the top, whilst the other is graduated from the wooden board at the base to the top, i.e. to a height of 1.5 16meters. On the side containing the seat the height of the child seated is measured, on the other side the child’s full stature. The practical value of this instrument lies in the possibility of measuring two children at the same time, and in the fact that the children themselves cooperate in taking the measurements. In fact, they learn to take off their shoes and to place themselves in the correct position on the pedometer. They find no difficulty in raising and lowering the metal indicators, which are held so firmly in place by means of the metal casing that they cannot deviate from their horizontal position even when used by inexpert hands. Moreover they run extremely easily, so that very little strength is required to move them. The little india-rubber balls prevent the children from hurting themselves should they inadvertently knock their heads against the metal indicator.

The children are very fond of the pedometer. “Shall we measure ourselves?” is one of the proposals which they make most willingly and with the greatest likelihood of finding many of their companions to join them. They also take great care of the pedometer, dusting it, and polishing its metal parts. All the surfaces of the pedometer are so smooth and well polished that they invite the care that is taken of them, and by their appearance when finished fully repay the trouble taken.

The pedometer represents the scientific part of the method, because it has reference to the anthropological and psychological study made of the children, each of whom has his own biographical record. This biographical record follows the history of the child’s development according to the observations which it is possible to make by the application of my method. This subject is dealt with at length in my other books. A series of cinematograph pictures has been taken of the pedometer at a moment when the children are being measured. They are seen coming of their own accord, even the very smallest, to take their places at the instrument.

Education, Serialized, a section of EduThirdSpace: The Newsletter, features retellings of how education has been viewed over the course of history from books, reports, letters, and so forth. The posts in this section are the words of the authors and not editorialized by me, Samantha, or anyone else. However, interpretation or commentary on the texts may be published in other sections of EduThirdSpace.